AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND = TAINO BURIAL GROUND

Ghosts of the Taíno

Mystery and controversy haunt a pre-Columbian ceremonial site in Puerto Rico.

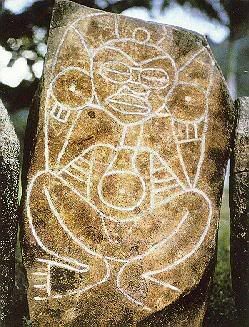

These images of Taíno gods, carved at least 500 years ago, have caused the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to radically alter dam construction plans on Puerto Rico's Portugues River. (Courtesy David Diener)

Archaeologist Chris Espenshade's instructions were clear: excavate a marginally interesting settlement (designated only as PO 29) along Puerto Rico's Portugues River that had once been occupied by the Taíno people, recover artifacts, record useful data, and get out. The bulldozers were waiting. After more than 20 years of budget delays, escalating costs, and engineering challenges, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers was finally ready to build the last phase of a $580 million flood control project that would protect Ponce, the island's fifth-largest city, from the devastating floods that sweep down the valley after heavy rains.

Then Espenshade, a consulting archaeologist with New South Associates in Stone Mountain, Georgia, and his team began turning up evidence of one of the largest, best-preserved pre-Columbian ceremonial centers known in the Caribbean.

Last summer, they unearthed a huge four-sided ceremonial plaza, a batey or ball court, measuring 130 by 160 feet. Other finds included a 90-foot-long artifact-laden midden mound, the first of what could be as many as 400 prehistoric burials, patterns of post holes that delineate ancient dwellings, and a 60-foot-long row of intricately carved granite and sandstone petroglyphs that appear to date to shortly before the arrival of the Spanish in the fifteenth century.

"When I went to the site right after the wall of petroglyphs had been exposed, my jaw just dropped to the floor," recalls co-investigator Peter Siegel, a specialist in pre-Columbian Caribbean cultures from Montclair State University. "I am five-and-a-half-feet tall and I was looking at a wall of well-executed carvings as tall as I am."

Staring back at Siegel from the stone slabs was a matched pair of full-length human figures: a man and a woman wearing a headdress and ear spools, arms outstretched, legs splayed in a frog-like stance, sexual organs clearly visible. He says the regalia shows that these were high-status people.

The discovery of the batey and other features prompted Espenshade to tell the Corps in June that the archaeologists would need more time and money to complete the work. Then he began finding burials in the midden mound and a west wall of the batey that suggested the plaza might be a lot larger than expected. The Corps agreed to another extension. And, as the summer wore on, another. Then, with the discovery of what Espenshade calls a "gallery of rock art" along the steeply sloping hillside at the site's northern boundary, it was clear a whole new strategy was needed.

"The north wall was just spectacular," says David McCullough a staff archaeologist with the Army Corps of Engineers Jacksonville district which includes Puerto Rico. "Once we realized that this was such an extraordinary site, I went to my engineer and told him we were going to have to shift from frantically trying to recover information to finding a way to preserve the site."

Future archaeology at the site is certain to have more direct Puerto Rican oversight. "Areas of the site that have not been excavated have a great research potential," says Tamara Gonzalez Vega, director of the Archaeological Council of Puerto Rico. "A more detailed archaeological investigation will proceed as soon as the dam's construction is finished."

But Espenshade is concerned about what remains in the ground. With only a small portion of the site excavated, reburial of the site is intended to assure that the artifacts, human remains, and petroglyphs stay in place for future study. For now the Corps has the site "heavily guarded," but the intense publicity generated by the discovery poses a new dilemma.

"I'm worried," he says. "We're only 15 to 20 minutes from downtown Ponce and everyone now knows what's here. Some of these glyphs would fetch tens of thousands of dollars on the antiquities market. If this site is not fenced and watched closely, somebody is going to come in with a backhoe some night and take everything."

Mike Toner is a freelance writer and former science writer for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

© 2008 by the Archaeological Institute of America

www.archaeology.org/0803/abstracts/taino.html

ARCHAEOLOGY AS COMMUNITY SERVICE: THE AFRICAN BURIAL GROUND

PROJECT IN NEW YORK CITY

By Warren R. Perry

"...it is our past, our culture and heritage, and forms part of

our present life. As such it is ours to control and it is ours to

share on our own terms." (Rosalind Langford 1983)

"The past is contested terrain over which archaeologists among

others struggle. How the past is conceptualized shapes our

perceptions of the present and what is possible in the future.

(Thomas Patterson 1993)

Introduction

Since its discovery in 1991, the African Burial Ground (ABG) in

New York City has been the subject of discussion in a variety of

scholarly and popular media (Wilson 1996). Its significance ranges

from the fact that its discovery gives voice to a marginalized

African historiography in the United States, to the window it

provides into

African captivity in the north. The ABG experience has inspired

public curiosity about both the African diaspora and the practice of

archaeological science. Through its public education programs it

continues to teach the descendant community to recognize and combat

improper research techniques and to identify cultural resources in

the cities and towns where they live. Finally, the ABG project has

provided the descendant community with political awareness through

concrete historical experiences that afford opportunities to make

alternative history and inclusion in the production of knowledge.

Recently, there has been some attention paid to the social

relations involved in the archaeological production of knowledge and

the movement of indigenous communities in demanding control of their

own past. These studies suggest that it is within the cultural

sphere that most struggles for identity and knowledge production

take place (Blakey 1983, 1991, 1996; Gero and Conkey 1993a and b;

Gathercole and Lowenthal 1994; LaRoche and Blakey 1996; Schmidt and

Patterson 1995; Perry 1996, 1997, in press; Perry and Paynter in

press). All scholars produce knowledge in specific sociocultural and

historical contexts. In this essay, the ABG will be situated within

the continuity of the African struggle that envisions a shared past,

empowering African descendants to challenge injustice and to demand

justice, dignity and power. The deeply sacred and symbolic role

played by the ABG in both past and present has spawned descendant

community outrage and unmasked institutionalized racism as

excavations commenced with callous indifference to the wishes of the

African community, both living and dead (Blakey 1996).

Here I will describe the racial tensions emanating from the

African Burial Ground from its 18th century inception to the

present, paying close attention to the conflicting relations among

the General Services Administration (GSA), archaeological

consultants and the ethical client, the African descendant

community. Chronicling these events and documenting these relations

is significant for evaluating claims to knowledge in order

to reveal the conditions under which that knowledge is produced

(Schmidt and Patterson 1995). The struggle around the ABG requires

coequal relationships and symmetrical exchanges of ideas and actions

between the scientific community and the African descendant

community. Only in this way can authority be established over the

ABG to create knowledge in the service of the community. The goal of

this essay is to show how public and scholarly engagement, part of a

legacy of African descendant activist scholarship, has become a

source of important insights into understanding and representing the

past and in contributing to the African descendant community's

understanding of itself.

The African Burial Ground: Legacy of Struggle

Early Resistance

The first African captives arrived in Dutch New Amsterdam in

1626 from West and Central Africa and later from Caribbean

plantations. Due to constant conflicts with Native Americans, the

Dutch created a buffer zone for themselves by granting

Africans "half-freedoms" and small parcels of farmland outside the

city walls about

1643. Since the ABG is located in this area, Africans may have begun

burying their dead there soon thereafter, although as yet there is

no conclusive documentary evidence of this. The marginal spatial

location and the respective marginal social positions of Natives and

Africans meant that their settlements were likely locales for

intercultural social and economic relations (Foote et al. 1993;

Taylor 1992).

When the British colonized New Amsterdam in 1664, the 700-plus

Africans constituted 40 percent of the population. This percentage

was greater than in any other English settlement except Charleston,

South Carolina, and more than was found in any northern settlement.

The British revoked African half-freedoms, instituted harsher

laws, confiscated African lands and imported more Africans for sale

to the south. There were a number of insurrections by Africans in

this area during the 18th century, and the highest proportion of

escapees with a greater likelihood of success than elsewhere on the

continent (White 1995). Indeed, individuals allegedly involved in

these revolts were executed at the ABG (Barto 1991; Will 1991). New

York gradually emancipated Africans from 1799 to 1827, but census

and court records indicate that slavery continued at least until the

1860s (Jaffe 1995).

The ABG is the oldest (late 1600s to 1796) and largest (five to

six acres) African descendant cemetery excavated in North America to

date. Situated near the banks of the Collect Pond, the ABG not only

provided privacy but its location near water was in keeping with the

common central African practice of associating cemeteries and bodies

of water (Foote et al. 1993; Thompson 1984). After 1750, several

noxious chemical

industries desecrated the ABG by disposing of their wastes there;

medical students at New York Hospital also stole corpses for

dissection. During the ABG occupation, Africans seem to have

controlled their own funerals, mortuary and burial practices, but

not without resistance (Blakey 1997; Foote et al. 1993; Harrington

1993; Jamieson 1995).

Furthermore, only during funerals were Africans permitted outside

after sunset and to gather in unsupervised groups larger than three

persons. In 1731 the British sought to curb African subversive

activity by passing laws requiring daytime burials with limited

attendance. Pawls (the cloth used to cover a casket during the

funeral and

procession to the grave site) and pall bearers were also banned at

African funerals (Epperson 1997). These laws suggest that the

British suspected that African funerals were used to mask insurgent

activity.

Recent Struggles

Today the ABG is located under some of the most valuable real

estate in the world. It is estimated that from 10,000 to 20,000

first-generation African Americans were buried in the ABG. Since

only 14,000 square feet were excavated, most of those interred

remain beneath the city. In 1989 the GSA sought to purchase a

block of land from New York City. The plan was to erect a $276-

million federal office building in lower Manhattan. Documentary

research conducted for the GSA by the Advisory Council on Historic

Preservation (ACHP) and NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC)

indicated the

presence of a "Negroes Burying Ground" on the proposed building

site. In 1991 GSA, as mandated by the National Historic Preservation

Act of 1966, contracted Historic Conservation and Interpretation

(HCI), an archaeology consultant firm, to begin fieldwork. The study

of the human remains was contracted to the Metropolitan Forensic

Team (MFAT) from Lehman College. As more human remains were

uncovered, GSA pressured HCI and MFAT to comply with the original

one-year construction schedule (Epperson 1997; Harrington 1993,

1996). Meanwhile, the descendant community held meetings, religious

observances, vigils and protests at the ABG (Blakey 1997).

Since the excavations began without any significant community

consultation or participation as to the treatment of the cemetery--

as required by the mandate of scientific requirements for the

preservation of the site's history--there was immediate and often

volatile reaction to the excavations by the African descendant

community (see the Kutz

video series for an account of these events).

In 1991 burials were disturbed by construction workers, further

alarming the African descendant community. Community persons who

were monitoring the excavations and had seen the remains at Lehman

College complained about the way the skeletons were being conserved.

Problems included remains wrapped in newspaper under improper

environmental conditions and inadequately stored on top of each

other (La Roche and

Blakey 1996). The descendant community condemned this behavior as

disrespectful, arrogant and insensitive. Their encounter with

contract archaeology made it clear that the few African American

archaeologists who exist were never consulted or involved in the ABG

research in any substantive way. It also became clear that

consulting firms reap huge profits from studying African Americans

and strongly influence how African Americans are historically

defined. These were major issues of concern and contention for the

African descendant community (LaRoche and Blakey 1996).

Since MFAT and HCI failed to produce a timely and comprehensive

research design, and had treated the remains unscientifically and

disrespectfully, the descendant community demanded that the remains

be placed under the care of Michael Blakey, one of the few African-

American biological anthropologists in the United States. Blakey,

who is a professor of anthropology at Howard University in

Washington, DC, was concerned that HCI and MFAT had no experience in

African or African American history, cultures or skeletal biology.

He was also aware that when archaeologists used construction

equipment to remove the earth down to the burial outline, they had

already destroyed artifacts that Africans customarily placed atop

their graves and coffins (Satchel 1997).

The descendant community, cognizant of the ignorant portrayals

of African diasporic history, recognized that archaeological

interpretation is an active and subjective struggle between

contending versions of history that demands political engagement

(Gathercole and Lowenthal 1994; Schmidt and Patterson 1995). To

insure that the spiritual, cultural and inspirational significance

of the site and its contents were subject to African-centered

paradigms and scholarship, they demanded incorporation of African

descendant voices and histories (La Roche and Blakey 1996). They

insisted that those working on the project have a knowledge of and

respect for African diasporic studies and a commitment to their

struggle to reclaim their past. For the descendant community, the

skeletal remains and the ancestral possessions are the only concrete

material evidence of the lives of this first

generation of African Americans in New York City. As such, they

constitute powerful links to a shared African past.

In 1992 David Dinkins, New York City's first African American

mayor, and U.S. Rep. Gus Savage of Illinois, who chaired the House

Committee for Building Funds, were able to establish an advisory

committee on the project, halt the excavation and close down the

site. At the request of the African descendant community, New York

State Senator David Patterson, who is also African American, formed

an oversight task force for organizing

various forms of political activity around the ABG (Howson 1992).

The descendant community continued to press for the involvement of

African American scholars in directing the research, analysis and

interpretation.

In 1993 Howard University gained control over the research

project and, along with John Milner Associates (JMA), another

contract archaeology firm, submitted a more comprehensive research

design to ACHP that incorporated the concerns and desires of the

descendant community. The archaeological materials were placed in

the Foley Square Lab under JMA, while the 400-plus human remains

were transferred to the Cobb Biological

Anthropology Laboratory at Howard University. Pageantry and

celebration accompanied the caravan of remains from New York to

Washington, DC, with stops at historically significant African-

American churches in several cities along the way. The transfer

culminated in a ceremony entitled "The Ties that Bind" at Howard

University.

The descendant community and its allies were in evidence throughout

the transfer celebration. Representatives from the African American

community, the U.S. Muslim community, the Native American community,

and from the Akan in Ghana were all in attendance at Howard. In

1994 African chiefs from Ghana returned to Howard on a

tour of fihankra, a movement of unity that involves prayers and

rituals for forgiveness to the ancestors to atone for colonial-era

involvement in the trade in African captives.

Although I have spoken of the descendant community throughout,

there is, of course, no homogenous African descendant community;

this entity is actually multi-dimensional and ideologically

heterogenous. Throughout the struggle around the ABG, however, all

segments of the African descendant community and their allies were

and continue to be involved. There continues to be a consensus that

the site, the human remains, the

artifacts and their interpretation must be controlled by the

descendant community.

The Current Research Project

The current scientific project constitutes yet another

dimension of the struggle for control of the ABG. We seek to

illuminate the impact of African captivity upon the lives of our

ancestors and their living descendants, and to reconstruct knowledge

of their origins and identities that were deliberately distorted in

the effort to bolster the identity of Euroamericans at the expense

of African Americans (Blakey 1997). As Scientific Director of the

African Burial Ground Project, Mi

chael Blakey has brought together a national and international

research team of scholars from Africa and the US who are concerned

with creating alternative histories. The ABG Project has evolved

into a multi-disciplinary scientific effort comprised of

complementary natural and social science teams with expertise in the

African diaspora. These include: molecular genetics, bone chemistry,

skeletal biology, history and archaeology (African and African

American), ethnology, conservation and African art history. This

collaborative effort has global and universal implications,

transcending any particular discipline or the interests of any one

segment of the descendant community.

These organizational changes have resulted in the selection of

four basic research questions to guide our scientific analyses. They

are relevant both for activist scholars and the descendant

community:

1) What are the cultural and geographical roots of the

individuals interred in the African Burial Ground?

2) What was the physical quality of life for Africans enslaved

in New York City during the colonial period

and how was it different from the quality of life in their African

homeland?

3) What biological characteristics and cultural traditions

remained unchanged and which were transformed during the creation of

African American society and culture?

4) What were the modes of resistance and how were they

creatively reconfigured and used to resist oppression and to forge a

new African American culture?

In addition to the scientific teams, the ABG has an Office of

Public Education and Interpretation of the African Burial Ground

Project (OPEI), directed by Dr. Sherrill Wilson. OPEI's primary

roles are to educate and inform the public of ABG project events, to

assure public access to the site, the skeletal and artifactual

remains,

and to allow appropriate cultural ceremonies to commemorate the

ancestors. It also provides community involvement/education

activities such as educators' symposia, laboratory tours and two

newsletters that update the public on the research and introduce

archaeology, anthropology and conservation to children and adults.

Conclusion

New York City's ABG project is a case of archaeology as

community service. It emerged from a protracted struggle over

control of the ABG and its products between an organized descendant

community and its allies, and the GSA and archaeology consultant

firms. This struggle has resulted in an increased awareness of the

disciplines of anthropology and archaeology within the African

descendant community. It has produced a public education program

that facilitates a reciprocal dialogue between researchers and the

general public, maximizing the interpretive potential of the

archaeological record and creating an historical consciousness that

challenges the distortions of Eurocentric history (Singleton 1995).

Through this struggle the descendant community and its allies

have successfully achieved the incorporation of African American

scholars in the creation and maintenance of a research design and

agenda that establish a prominent role for historically under-

represented African Americans in the analysis and interpretation of

an internationally renowned archaeological site (Mathis 1997). By

taking moral

responsibility for the spiritual and physical control of the site,

the descendant community seized intellectual power--forcing changes

in the composition and direction of the professional leadership of

the project (La Roche and Blakey 1996). The original, ancestral ABG

community and the modern descendant community have used this sacred

social space to resist and to honor their African heritage in spite

of institutionalized racist disrespect. The struggle for the proper

treatment of the ABG reaffirms its significance in the past and

gives the site continued significance in the present; it is an

important part in the legacy of struggle to control and interpret

the African past (Blakey 1996).

References

Barto, S. 1991. Chain of Title Block 154 (Principally) Northern

Half. Unpublished Historical Research Reports for the African Burial

Ground Project. Historic Conservation and Interpretation (HCI). On

file with the African Burial Ground Project.

Blakey, M.L. 1997. The New York African Burial Ground Project: an

examination of enslaved lives, a construction of ancestral ties.

Briefing prepared for the Sub-commission on Prevention of

Discrimination and Protection of Minorities Commission on Human

Rights, United Nations. Delivered at the Palais des Nations,

Geneva Switzerland, 19 August.

--1996. Howard University research reaches a new plateau.

Newsletter of the African Burial Ground and Five Points

Archaeological Project. 1 (10):3-7.

--1991. Man and nature, white and other. In Harrison, F. ed.

Decolonizing Anthropology. pp. 15-23. Washington DC:

American Anthropological Association.

--1983. Socio-political bias and ideological production in

historical archaeology. In Gero, J.M., D.M. Lacey and M. Blakey,

eds. The Socio-Politics of Archaeology. Research Report #23,

Department of Anthropology. U Mass. Amherst.

Epperson, T.W. 1997. The politics of "race" and cultural identity at

the African Burial Ground excavations, New

York City. World Archaeological Bulletin. 7:108-117.

Foote, T.W., M. Carey, J. Giesenberg-Haag, J. Grey, K. McKoy, and C.

Todd. 1993. Report on Site-Specific History of Block 154. Written

for the African Burial Ground Research Project. New York.

Gathercole, P. and D. Lowenthal, eds. 1994. The Politics of the

Past. New York: Routledge.

Gero, J. and M.W. Conkey. 1993a. Engendering Archaeology: Women and

Prehistory. Basil Blackwell.

--1993b. Tensions, pluralities and engendering archaeology. In

Gero, J. and M.W. Coney, ed. Engendering Archaeology: Women and

Prehistory. pp. 3-31. Basil Blackwell.

Harrington, Spencer. 1993. New York's great cemetery imbroglio.

Archaeology. March/April. pp.30-38.

--1996. An African cemetery in Manhattan. In Fagan, B. ed.

Eyewitness to Discovery. pp. 324-333. London: Oxford U Press.

Howson, J.E. 1992. The Foley Square Project: An 18th century

cemetery in New York City. African American

Archaeology. Newsletter No. 6, Spring. pp.3-4.

Jaffe, S.H. 1995. "This Infernal Traffic": New York Port and the

illegal slave trade. Seaport: New York's History Magazine. 29 (3):36-

37.

Jamieson, R.W. 1995. Material culture and social death: African-

American burial practices. Historical Archaeology. 29 (4):39-58.

Kutz Television, Inc. 1994. The African Burial Ground: An American

Discovery. Parts I-IV. The National Technical Information Services,

National Audio Visual Center, VA.

Langford, R. 1983. Our heritage--your playground. Australian

Archaeology, 16, 1-6.

La Roche, C.J. and M.L. Blakey. 1996. Seizing Intellectual Power:

the Dialogue at the New York African Burial Ground. Paper, pp. 1-48.

Mathis, R. 1997. The Harris Matrix as a useful method in the

stratigraphic analysis of the African Burial Ground. Unpublished

Draft-Statement of Field, for the Department of

Anthropology, U Mass, Amherst.

Patterson, T.C. 1993. Archaeology: The Historical Development of

Civilizations. Prentice Hall.

Perry, W. In Press. Dimensions of power in Swaziland research:

coercion, reflexivity and resistance. In Transforming Anthropology.

A Publication of the Association of Black

Anthropologists, Virginia, Arlington.

--1997. Analysis of the African Burial Ground Archaeological

Materials. Update: Newsletter of the African Burial Ground and Five

Points Archaeological Projects, Vol.

2 #2:1-5 & 14.

--1996. The African Burial Ground Project. African Update:

African Studies Newsletter Vol. IV, # 4:1-5. CCSU, New Britain, CT.

Perry, W. and R. Paynter. In press. Epilogue: Artifacts, Ethnicity

and the Archaeology of African Americans. In Singleton, T., ed. We

Too Are America: Essays in African American Archaeology.

Charlottesville, VA: University Press of Virginia.

Satchel, M. 1997. Only remember us: skeletons of slaves from a New

York grave bear witness. U.S.News and World Report. July 28:51 and

54.

Schmidt, P.R. and T.C. Patterson. 1995. Making Alternative

Histories. The Practice of Archaeology and History in Non-Western

Settings. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press.

Singleton, T.A. 1995. The Archaeology of Slavery in North America.

In Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol. 24, pp. 119-140.

Taylor, R. 1992. Land of the blacks. New York Newsday. Thursday,

February 6. p.60.

Thompson, R.F. 1983. Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American

Art and Philosophy. New York, Vintage.

White, S. 1988. We dwell in safety and pursue our honest callings:

free blacks in New York City, 1783-1810. The Journal of American

History. 75 (2):445-470.

Will, G. 1991. Salvage archaeology in Manhattan offers a

perspective about America. Hartford Courant.

Wilson, S. 1996. Citations on the New York African Burial Ground

1991-1996. (3rd Ed.) Compiled by the Office of Public Education and

Interpretation of the African Burial Ground. New York City.